I’d say on balance that most people would like to romanticise the place they live in. I, of course, am no exception to this, and have spent (wasted?) countless hours trying to establish literary and cinematic connections with my corner of the Smoke. In all honesty, I can state with authority that knowing the myths that come with the territory hasn’t really got me very far, but it has- and this is a big ‘but’- made trips to the shops that little bit more exciting.

I’d say on balance that most people would like to romanticise the place they live in. I, of course, am no exception to this, and have spent (wasted?) countless hours trying to establish literary and cinematic connections with my corner of the Smoke. In all honesty, I can state with authority that knowing the myths that come with the territory hasn’t really got me very far, but it has- and this is a big ‘but’- made trips to the shops that little bit more exciting.

My locale is hardly the most “vibrant” of urban settings, but it is surprisingly rich in cultural connotations. From the block of flats where Catherine Deneuve has her meltdown in Polanski’s Repulsion to the bric à brac shop where Nicola Six holds down a brief job in Martin Amis’ London Fields, this part of West London has enough micro-landmarks to fill an Iain Sinclair anthology. The other night, I was preparing to get off the Tube at Earl’s Court station when I reached a page of the book I was reading that placed me just metres away from where the narrator was standing:

Our basement flat was in a side street not far from the Earl’s Court Road, just a few minutes’ walk from the tube station. It was a lively area, a little overcrowded, a little seedy; its restless bustle and activity could sometimes be a little overwhelming, but this afternoon it really lifted my spirits. Suddenly, I began to feel, for the very first time, that I might be setting out on a great adventure.

My eyes lit up at this passage from Jonathan Coe’s Thatcher-era roman-not-quite-à-clef What a Carve Up!. Better still, he goes on to describe precisely the journey I had just made in reverse:

Getting from Earl’s Court to St Pancras required a tedious journey of twenty minutes on the Picadilly Line. As usual, I had a book open in my hands, but I couldn’t concentrate on it.

Wow! He was, like, on the same train as me, just going the opposite direction! In 1982! I had a book I hadn’t been concentrating on, too- and it was this book! Of all the coincidences, etc, etc… you see my point. It’s all quite fun, if a bit… aimless. Regular readers should by now expect nothing else.

Anyway, Jonathan Coe is far from the first novelist to transcribe Earl’s Court and its environs into literary narrative. As far as my limited knowledge strecthes, the first truly great Earl’s Court novel is probably Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square, published in 1941 and set several years before, when Moseleyite blackshirts pranced up and down the already-congested thoroughfares of SW5. I was explaining to someone today that I read it shortly after arriving in the area, and immediately identified with its aimless, alcoholic protagonist George Harvey Bone. If you’ve read the novel, you’ll realise that this was probably rather unhelpful. Hanging around the pubs of the Earl’s Court Road- The Prince of Teck, The King’s Arms, Ashbee’s- looking a bit sad started to feel like a grim duty. Then somebody told me that it was stupid to blindly take messages from books. I blindly took the message from them and started hanging around the pubs of Soho looking a bit sad instead.

This is incidental, though; magnificent as Hangover Square is, it is not the great Earl’s Court novel. That mantle falls to another work written about an area unrecognisable from Hangover Square’s SW5 in all but its bedsitting transience, a London book as demanding and subtle as any I have ever read.

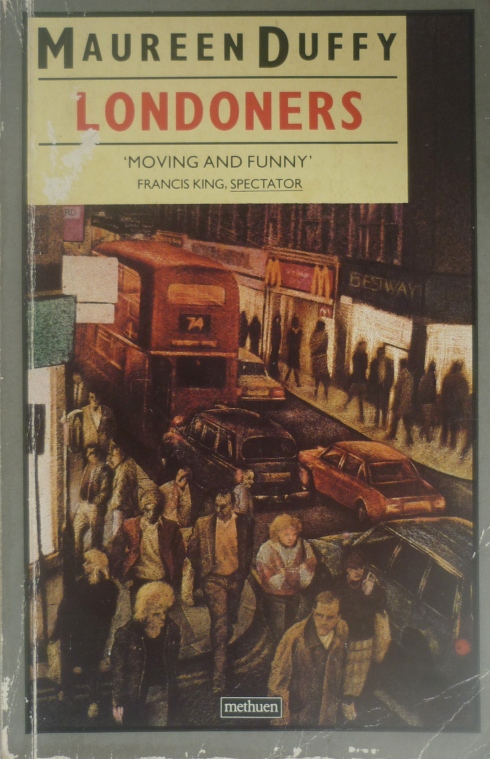

I was idling an afternoon away in the Trinity Hospice Bookshop on Kensington Church Street early this Summer when I chanced upon the spine of Maureen Duffy’s Londoners. I recognised neither the author’s name nor her style as I flicked through its pages. What I did recognise, though, was the bus that goes past my house on the jacket illustration. The 74 in a novel? Blimey…

I looked harder and saw the Earl’s Court Road branch of McDonald’s, the now-closed branch of Bestway where I used to buy two-fingered KitKats for 15p… and the book itself wasn’t going for that much more. I handed over my small change to the perpetually pissed-off shopkeeper and headed out to the park to make a start on it.

The writing threw me a bit at first, I must admit; Duffy writes from the perspective of ultra-anti hero Al, a fiftysomething failure of an academic with a corrosive passion for the work of Medieval Parisian poet François Villon. Al lives in a room in one of the mansion blocks up from the junction between the Earl’s Court and Old Brompton Roads, and scrapes by on hack work commissioned by soon-to-be-defunct periodicals and rues everything from the decline of English Socialism in the wake of stage-one Thatcherism to his own, utterly directionless existence. He’s not so much an unreliable narrator as a completely unmotivated one- so much so, in fact, that there is little reason to disbelieve what he tells us. Little happens, yet he draws the reader in with highly-stylised prose and pithy observations on his neighbours, flat beer, and, of course, Villon, the ‘Frank master’ whom he often addresses directly. He is a pathetic figure, a fatalist, a bovarist and, it soon becomes clear, a self-deluding alcoholic; and yet, despite his affectations, he remains an extremely sympathetic and very funny guide through the petty crime, abandoned ambitions and interweaving homosexual passions of Earl’s Court circa 1983.

Everything Al sees takes on a literary significance; he is at times extremely pompous, a character simply too well-read to function outside of the small circuit of drinking hubs and libraries around his lodgings:

They all come to London, not England. That’s what they call it; that’s the allure. I remember an Australian returned for a sentimental trip reliving: ‘I loved London but the poverty and the cold made me go back.’ At once the city is Dickensian… I go out into the street again where the rain’s stopped; starless, unmooned, the sky is a cloudrace. I conjure pathetic fallacies all the time: the adult version of not treading on the black lines to hold off bad luck I suppose.

As a local, one of the great pleasures comes from Al’s often bathetic descriptions of his haunts. For anyone who’s ever exited the Underground onto the Earl’s Court Road on an unsympathetic November evening, the following passage may not read quite so absurdly as at first its language might suggest:

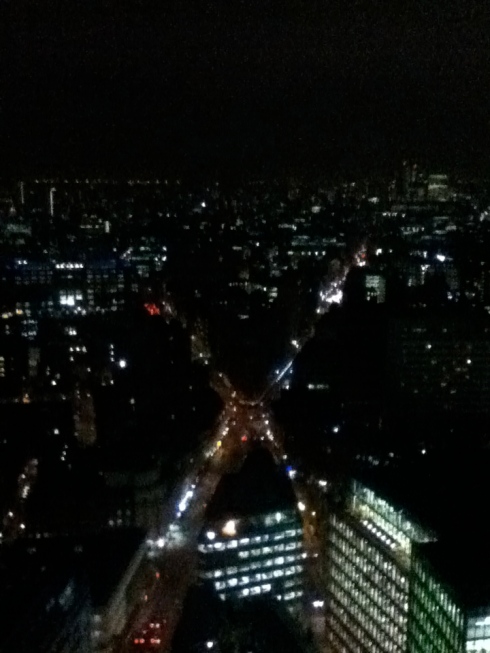

…by the time I come out of the tube at the other end, a worm of meat extruded by the mincer, the cloud has thickened and towers over the rush hour street a chill wind funnels down, blowing wrappers, hurriers-home with turned-up collars, dogends, plastic cups along the traffic stream. The wind at my back, I’m bowled along too. On the corner flower stall freesias freeze in their cellophane jackets , daffodils tremble in their buckets. The seller stands massive in a lit doorway waiting for anyone brave enough to stop and be whipped cold... Hopper, for instance, could have caught her there as she stands, forever. I need a great figurative to hold this city now. Perhaps I should advertise in Creative & Media Appointments: destitute writer wants mad painter for hopeless project.

Elsewhere, the traffic on the Earl’s Court Road is ‘surrendered completely to traffic. Great congers, hammerheads, bluefins of pantechnicons and artics full-bellied shudder and deafen the walkers going south in a shoal of minnow cars for the river crossings’; a walk to a debate at Kensington Town Hall in Campden Hill Square takes him ‘beyond the tube station where the stream grows quieter and we wait to cross the dusty veldt of the Cromwell Road, whose plane trees pattern the air with their still lifeless tracery.’; at night, ‘the air is aromatic with fish and chips, roast meat from the great turning drums of Kebabed flesh, curry in battered samosa triangles, glossy with grease, and from the stainless steel vats of hot chick peas, mutton, ladies’ fingers, saffron rice’, much as it still is on any given night of the week round here.

The novel is one the funniest, most painfully accurate articulations of detrimentally literate male stasis I know of. Identify yourself as a character in a novel, with all the pseudo-intellectual trappings and imagery that entails, and cyclical fatalism is all but inevitable. I’ve searched long and hard for other novels by Duffy, but so far haven’t had any luck. She is chiefly known as the great lesbian author of the 1960s, but her first-person male narrative in Londoners is up there with the best I’ve ever read- and I’ve read a lot of first-person male narratives. More relevant to this post, though, is the fundamental importance of existing local boundaries to the novel’s structure; Al rarely leaves Earl’s Court, and treats his rare excursions into London as perilous treks. 1980s Earl’s Court is to him, he has decided, what 15th Century Paris was to Villon.

Other areas have their latter-day myths and legends, too, of course; as the aforementioned Iain Sinclair writes in his essay X Marks the Spot (collected in Lights out for the Territory):

We are all welcome to divide London according to our own anthologies: JG Ballard at Shepperton; Michael Moorcock at Notting Hill; Angela Carter- south of the river, Battersea to Brixton, where she hands over to the poet Alan Fisher; Eric Mottram at Herne Hill; Robin Cook’s youthful self at Chelsea, while his fetch minicabs between Soho and the suburbs (meeting Christopher Petit who is making the reverse journey); John Healy sparring down Caledonian Road towards the “grass arenas” of Euston; Peter Ackroyd dowsing Clerkenwell; James Curtis in Shepherd’s Bush; Alexander Baron in Golders Green; Emanuel Litvinoff and Bernard Kops disputing Whitechapel and Stepney Green with the poets Bill Griffiths and Lee Harwood; Stewart Home commanding the desert around the northern entrance to Blackwall Tunnel; Gerald Kersh drinking in Fleet Street; Arthur Machen composing The London Adventure or the Art of Wandering…

… Not to mention Colin McKinnes in W10, Roland Camberton in Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia, Zadie Smith in Willesden, Sinclair himself in Hackney… there would be a great psychogeographical map to be made of all this, were the list not so long and the territory so disputed. If you know of any such thing, I’d very much like to hear…