Battersea isn’t a glamorous part of London. What little recognition it gets outside of its boundaries focuses on Giles Gilbert Scott’s iconic power station (which isn’t even in Battersea) and the cruel-but-sort-of-true ‘South Chelsea’ jokes suffered by its famous red trouser brigade. It’s an in-between place, separating capital-W West London from South London proper.

I know lots of people my age who live here; none of them fit the guffawing sloane stereotype. They’re cash-strapped young professionals rather than trustafarians, people who don’t see the sense in stumping up the deposit for a bedsit with no lav in Earls Court or a hyper-inflated rent in Hackney.

There are still some extremely deprived areas in Battersea. But in terms of bourgeois attractions, it’s home to some awful, awful night spots, a first rate Vietnamese restaurant and an unfortunately mis-attributed mainline railway station. It’s getting a tube station. Battersea is residential, unremarkable and fairly central. Few places evoke the phrase ‘it’ll do – for now’ quite like it.

But for a long time, Battersea was a poor borough with a history of radicalism and progressive politics. In 1892, the constituency elected the union activist John Burns, who had been arrested on numerous occasions for ‘sedition and conspiracy’ as an independent Labour MP. He later became one of the first working class cabinet members, before resigning from government in August 1914 in protest at the declaration of war.

In 1913, while Burns was representing Battersea’s interests at a national level, John Archer, a liverpudlian of Barbadian extraction, was elected to head the council, becoming Britain’s first black mayor. Archer stayed active in local politics until his death in 1932, and was instrumental in Shapurji Saklatvala’s historic electoral victory in Battersea North in 1922. Representing the area until 1929, Saklatvala was one of only four members of the Communist Party of Great Britain to win a seat in the Commons. Imagine that happening in ‘Nappy Valley’ now.

It’s also racked up a respectable number of pop culture references. There’s Black Hearts in Battersea, of course, and Up the Junction (as in ‘Clapham’) is another obvious one; a great panorama over Chelsea Bridge and Manfred Mann’s title music make it a must for this piece:

Norman Foster’s Albion Riverside complex played on-screen house to Hugh Laurie and Joely Richardson in what might be the worst film I’ve ever seen, Ben Elton’s Maybe Baby. Money shots of Albert Bridge are not in short supply: (for masochists only, this)

Here’s Richard Burton keeping a low profile at the labour exchange in Martin Ritt’s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold:

Richard Burton at ‘Battersea Labour Exchange’ (probably a studio set) in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (Martin Ritt, 1965)

Burton returned to nearby Nine Elms six years later in a cult video nasty called Villain, in which he played a gangland psychopath:

Musically, SW11 offers a lot but delivers little. Latchmere by the Maccabees is about a swimming pool in south Battersea. I’d post a video, but having just listened to it for the first time in seven years, I’m not going to. (It’s not very interesting, but nor is it as stand-out bad as the trailer for Maybe Baby.) Squeeze’s Up the Junction is decidedly Clapham-centric, so it wouldn’t count even if it weren’t shit. Babyshambles recorded a characteristically terrible song called Bollywood to Battersea and Morrissey’s You’re the One for Me, Fatty (‘All over Battersea/Some hope and some despair’) isn’t much cop, either. Better is the Super Furry Animals’ Battersea Odyssey:

So Solid Crew came from the soon-to-be-demolished Winstanley Estate, near Clapham Junction. (A link between Manfred Mann and Asher D – who’d’a thunk?) The cover of Irish new wave group Microdisney’s first album is a shot of the World’s End towers in Chelsea, taken from Battersea Bridge. For no reason other than its wonderful opening lines, here’s a song from it:

My correspondent acb of this:

This is without mentioning this godawful Petula Clark ode to Battersea Park from 1951:

It’s connected to the U-world by three magnificent bridges – from east to west, the Chelsea, the Albert and the Battersea. In the Londoner’s imagination, the two most central of these are inextricably linked to the grandeur of the north shore, the first by name association, the second by dint of its high-maintenance beauty and unreliability in times of need; the cameramen on Made in Chelsea are keen on dropping in shots that ogle its suspension. Happily, this distracts viewers from the ghastliness of the cast. But to the Royal Borough, Battersea is welcome to its eponymous river crossing. Jospeph Bazalgette’s bridge of 1890 is a sturdy, practical design that, by comparison to its society neighbours, feels like a staff exit. It’s thin and busy, and due to the restrictions on the Albert, often constipated with traffic.

But to the Royal Borough, Battersea is welcome to its eponymous river crossing. Jospeph Bazalgette’s bridge of 1890 is a sturdy, practical design that, by comparison to its society neighbours, feels like a staff exit. It’s thin and busy, and due to the restrictions on the Albert, often constipated with traffic.

On the south eastern corner, there’s a slippery staircase which leads all the way down to the sludgy beach. This liminal slip of not-quite land can’t help but remind me of the characters in Penelope Fitzgerald’s Offshore, which is set on a group of houseboats just a little further down the river. My shoes sink into the slime and beer cans rattle over the mud in the wind. Even with the architectural cupcakes of Chelsea in sight, it’s bleak as hell.

On the north shore, there’s a small garden that leads down to a balcony, from where you can throw stuff at low flying pigeons. From the parapet of the bridge, a statue of James McNeill Whistler, who painted the bridge and the stretch of river around it numerous times after moving to London in 1859.

The American painter’s depictions of Old Battersea Bridge are interesting, to say the least. He described Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge, the most famous – and most exciting – of these, as ‘an artistic interest alone, divest(ed) of any anecdotal interest that might otherwise have been attached to it.’

Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge (James McNeill Whistler, c.1872-75) (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

He had painted the bridge in a more naturalistic style shortly after arriving in London:

From a 21st Century perspective, the later painting seems almost hallucinatory; the supports are stretched out of all realistic proportion, turning the squat, rickety wooden structure of the earlier painting into a towering, awe-inspiring arch. Could the figure by the boat – is he pulling it in? – at the base of the support be one of the men we see pushing out a similar vessel a decade before? He’s there to show the distortion of scale, just as the figures in Brown and Silver provide a measure of perspective.

Meanwhile, a dusting of gold illuminates the masts of the tall ships further down the river. Whistler would take this disintegrating firework effect further in the extraordinary Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket of 1875. The painting depicts a celestial explosion of lights over Cremorne Gardens, just upstream from Battersea Bridge. It was the last of his London Nocturnes, and by far the most controversial.

Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket (James McNeill Whistler, 1875) (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

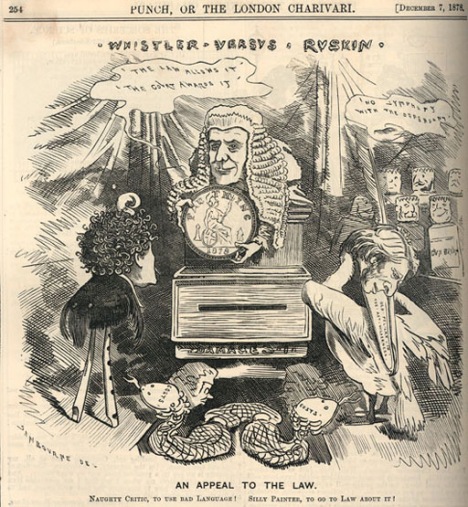

Unsurprisingly, the endlessly tiresome John Ruskin didn’t approve. When the painting was shown at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877, Ruskin’s review of the exhibition dismissed Whistler as a ‘coxcomb’ and expressed exasperation at the artist asking ‘two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.’ Having slagged off a fair few contemporary artists in reviews myself, I can understand the temptation to write nasty things about cocky stylists. But Ruskin really did make an arse of himself with this one.

Nevertheless, the review severely damaged Whistler’s reputation; patrons abandoned him and sales dried up. In 1878, the notoriously hostile artist sued the critic for libel, initiating a farcical court case. The jury ruled in favour of Whistler, but awarded him only token compensation; the action contributed significantly to his declaration of bankruptcy the following year. It would take a long time for him to re-establish himself.

But back to Battersea, and a detour back inland to Lavender Hill. Rarely do you see such a vast swathe of low rise buildings in inner London. While Whistler and Ruskin were battling for their reputations at the High Court, Victorian developers were knocking up a modern town. The population rose from 3,000 in 1801 to 169,000 a Century later. Huge agricultural estates were sold to speculators, and terrace after terrace sprung up in the hinterland of the old riverside settlement to accommodate the influx of labourers. Stretching from the river to Clapham Common, the borough looks much as it did then. The contrast with the deranged hedgehog of development on the horizon is astonishing.

As our old friend John Archer told his constituents in his 1913 victory speech,

‘Battersea has done many things in the past. But the greatest thing it has done has been to show that it has no racial prejudice and that it recognises a man for the work he has done.’

Even apparently uninspiring and drab places can be rather remarkable.